Star Wars: Fate of the Old Republic Looks Years Away — and That’s the Point of Announcing It Now

A Reveal Built on Promise, Not Proof

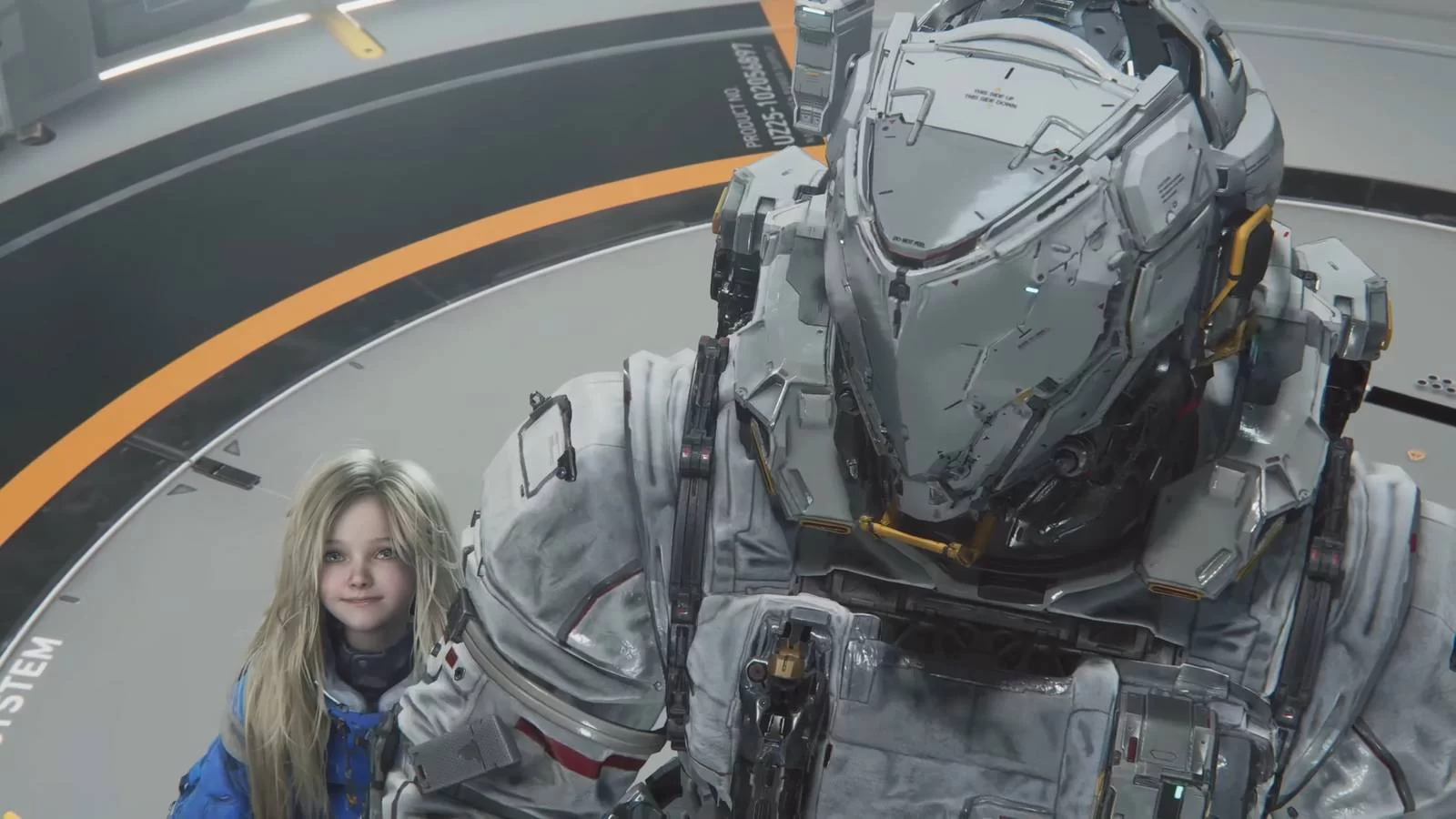

Star Wars: Fate of the Old Republic has been positioned as a spiritual successor to Knights of the Old Republic—language that immediately summons a very specific kind of expectation: party-driven decision-making, consequences that actually stick, and a story that treats your choices as part of the canon of your run. It’s also being described as a single-player, narrative-driven action RPG where decisions truly matter.

That pitch is enough to light up a fanbase on announcement alone. But a key detail reframes everything: the studio leading the project, Arcanaut Studios, was formed in 2025, meaning the game likely hasn’t even had a full year of development behind it. A public estimate circulating puts 2030 as an “optimistic” target—delivered with the kind of gallows humor that ends in “maybe it’s a PlayStation 7 game.”

It’s easy to treat that as bad news. The more useful read is this: this is what modern AAA reveals look like when they’re essentially hiring ads and brand statements. And Star Wars—especially the Old Republic era—has become the kind of brand where that tactic is increasingly common.

Context: KOTOR’s Shadow Is Both a Gift and a Trap

A “spiritual successor” to KOTOR isn’t merely a genre label. It’s a promise to chase a particular feeling: moral choice under pressure, companions who aren’t just combat kits, and a galaxy that responds to your identity.

The irony is that the very thing that makes this reveal exciting is what makes the project so hard to ship. KOTOR’s reputation has only grown over time; nostalgia has solidified into a kind of canon. That creates a tightrope:

-

If the game leans too hard into modern action RPG conventions, fans may claim it missed the point.

-

If it leans too hard into retro CRPG structure, it risks feeling niche in a modern blockbuster market.

-

If it tries to do both, it risks scope creep—the silent killer of long projects.

So when people hear “2030,” they’re reacting to the wait. They should also be reacting to the ambition implied by the phrase “decisions truly matter.”

Why Announce So Early? Because the Reveal Is Doing Multiple Jobs

When a project is early, a reveal typically isn’t about selling this year’s product. It’s about shaping the next five years of perception.

H2: Job 1 — Recruiting at scale

Big narrative RPGs are talent-hungry. You don’t just need engineers and designers; you need quest writers, cinematic teams, systemic designers for consequence tracking, UX, combat specialists, encounter designers, and a production pipeline that can survive constant iteration. Announcing early helps a new studio look “real” to hires in a competitive market.

H2: Job 2 — Securing long-run confidence

If you’re pitching investors, partners, and licensors, attaching a high-profile name and brand can be the difference between “interesting startup” and “serious long-term production.” A Star Wars single-player RPG isn’t a casual bet; it’s a multi-year commitment.

H2: Job 3 — Planting a flag against “single-player is dying” narratives

When a major sci-fi brand announces a choice-driven single-player RPG, it’s a cultural statement: there is still a market for big narrative games that aren’t live-service. That matters for industry morale and player trust—at least temporarily.

The problem is that early reveals also create a new enemy: timeline cynicism.

Technical/System-Level Explanation: Why “Choices That Matter” Takes Forever

Players hear “choices matter” and imagine alternate endings. Developers hear “choices matter” and see an exploding spreadsheet of dependencies.

To make meaningful choice systems work, the game needs more than branching cutscenes.

H3: 1) Persistent state tracking

Every major decision becomes data that can affect:

-

who is alive

-

which factions trust you

-

what areas open or close

-

what companions stay or leave

-

what resources you gain

-

what the final act even looks like

That requires robust tools, testing discipline, and an architecture that can handle edge cases without collapsing into bugs.

H3: 2) Content multiplication

Branching narratives don’t scale linearly. One fork becomes two quests, then four, then eight. Studios often “reconverge” branches to keep scope reasonable—but doing so without making choices feel fake is a craft problem, not a checkbox.

H3: 3) Action RPG combat complicates iteration

Pure narrative games can iterate quickly on writing and scene flow. Action RPGs also require:

-

combat feel and balance

-

enemy behaviors

-

encounter readability

-

camera and controls

-

progression pacing

That’s months of tuning even when the narrative is stable. When narrative changes late, combat contexts change too—new enemies, new locations, new tools, new pacing.

So the “not even a year in development” detail is huge. It implies the team is likely still defining pillars, building tools, prototyping combat, and figuring out what “Old Republic spiritual successor” means in 2025’s action RPG landscape.

Player Impact: Announcement Fatigue Is Real (and Rational)

A lot of players don’t hate long dev cycles; they hate long dev cycles marketed like imminent releases.

That’s why some reactions frame early announcements as “non-news,” especially without gameplay footage or even a real window. The emotional logic is simple:

-

If it’s not playable soon, it can’t be part of my near-term hype.

-

If it’s too early, it might be canceled.

-

If it’s too early, everything could change.

That last part is important. When a game is truly early, your mental picture of it is mostly fantasy. Fans fill the blank space with what they want, not what’s real. And later, when the actual design reveals itself, that mismatch becomes resentment.

Industry Strategy Analysis: Why “2030 Optimistic” Can Still Be a Smart Reveal

If you assume the game’s horizon is far, the reveal can be read as positioning:

-

It reassures players that single-player Star Wars RPG ambitions aren’t dead.

-

It gives the studio time to build a community without locking itself to a near-term promise.

-

It allows gradual marketing: concept art, dev diaries, a first gameplay slice years later.

The risk is that this kind of long runway increases scrutiny. Every quiet year becomes its own narrative. Every industry layoff cycle sparks “will it survive?” speculation. And Star Wars projects, historically, tend to carry extra pressure because expectations are loud and the brand is unforgiving.

Future Outlook and Risk Analysis: The Two Real Threats

The joke about “half the time they get canceled” lands because it’s not just a meme; it’s a pattern of modern AAA.

H3: Threat 1 — Scope drift

A spiritual successor label can balloon features: deep companions, branching morality, multiple endings, reactive worlds, cinematic production values, action combat, platforming, puzzle systems—each one expensive.

H3: Threat 2 — Time itself

The longer a project runs, the more it risks:

-

leadership changes

-

engine/tool changes

-

market shifts

-

platform transitions

-

rising budget pressure

A game that might target 2030 is also a game that has to survive multiple industry cycles. That’s the hard part.

If Fate of the Old Republic makes it, it won’t be because the reveal was exciting. It’ll be because the studio can lock its core pillars early, resist feature bloat, and build a production pipeline that turns “ambitious promise” into shippable reality.